Oxidizing FreeBSD's file system test suite

TL;DR More than 100× faster than the original, with more features and better configurability!

Your proposal Rewrite PJDFSTest suite has been accepted by Org The FreeBSD Project for GSoC 2022.

So, here we are! My proposal for the Google Summer of Code has been accepted, and so start a long journey to rewrite this test suite! But what this project is about, why rewrite it in Rust anyway?

In this post, I will answer to these questions, by explaining what is the project, its current shortcomings and how rewriting it in Rust has solved them.

Thanks

These introductory words are to thank my mentor Alan Somers, for accepting the proposal, helping and guiding me through this journey! His high availability and his contributions helped me a lot to do this project! I also want to thank all the crate maintainers who allowed this project to be created and the authors of the original test suite!

Code

The code is available on GitHub.

What is pjdfstest?

First, pjdfstest is a test suite for POSIX system calls. It checks that they behave correctly according to the specification, e.g. return the right errors, change time metadata when appropriated, succeed when they should, etc. It’s particularly useful to test file systems, and mainly used to this effect.

In fact, it was originally written by Pawel Jakub Dawidek to validate the ZFS port to FreeBSD, but it now supports multiple operating systems and file systems, while still primarily used by the FreeBSD project to test against UFS and ZFS file systems.

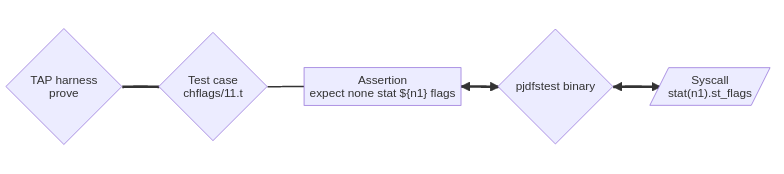

Its tests are written in Shell script and relies on the TAP protocol to be executed, with a C component to use syscalls from shell script, which we are going to see in more detail in the next section.

TAP is a simple protocol for test reports.

Even if it’s supposed to test POSIX syscalls, some non-standardized like

chflags(2)are tested as well.

Architecture

Like explained earlier, the main language for the test suite is Shell script. This is a high-level language, available on multiple platforms and with a simple syntax if we consider the POSIX-compatible subset.

However, it’s impossible to rely solely on it to test syscalls since it doesn’t have bindings to call these functions directly. Even if most syscalls have binaries counterparts, what should be tested is their implementations.

pjdfstest.c

This is where the pjdfstest program comes useful.

It acts as a thin layer between syscalls and shell, by providing a

command-line interface similar to how these syscalls should be called in C.

It returns the result on the standard output,

whether that be a formatted one like for the stat(2) output,

an error string when a syscall fails, or 0 when all went well.

For example, to unlink(2) a file: ./pjdfstest unlink path

which should return 0 if the file has been successfully deleted,

or ENOENT for example if it doesn’t exist.

The program isn’t used directly by the test cases,

but through the expect bash function.

Test case

The test cases are plain shell scripts which contains assertions.

An assertion is a call to the expect bash function, which takes as parameters the expected output

and the arguments to be forwarded to the pjdfstest binary.

The binary then executes the syscall and send its result back to the expect function,

which compares the output with what’s expected,

and fails when it should.

The typical shape of a test case is:

- Description

- Feature support

- TAP plan

- Assertions

Example:

tests/chflags/11.t

# Description

desc="chflags returns EPERM if a user tries to set or remove the SF_SNAPSHOT flag"

dir=

# Check feature support

# TAP plan

# Assertions

n0=

n1=

n2=

cdir=

for; do

if [; then

Execution

The cases are grouped in folders named after the syscall being tested.

Since they’re shell scripts, the test cases could be launched directly,

but they still need a TAP harness for the assertions to work.

They are usually executed through the prove harness

(which is commonly included with perl).

Architecture’s chart

Limitations

This architecture has its advantages, like readable tests or quick modifications, but several limitations also arise from it.

Configurability

Some features (like chflags(2)) aren’t systematically implemented on file systems,

often because they aren’t part of the POSIX specification.

To account this, the test suite has a concept of features.

However, the supported configurations were hard coded in the test suite and consequently couldn’t be easily configured, like with a configuration file or the command-line.

It also can’t skip tests correctly. The tests to be skipped just have their TAP plan rewritten to send “1..1\nok 1”, which hardly give feedback to the user that the test wasn’t executed.

Isolation

A lot of assertions are written in a single file. This is due to the TAP-based approach which encourages large tests instead of small isolated ones, but also because it’s harder to split and refactor a shell script.

Another problem is that some tests needs privileges to be run. Because it assumes that the current user is the super-user and doesn’t make distinction with the parts requiring privileges, it’s impossible to know which parts fail because of the lack of rights.

Also, given the lack of isolation between these assertions, it’s more difficult to debug errors.

Debugging

As a consequence of large test files, it’s difficult to understand what went wrong in case of failure. Also, writing tests in shell script made them easy to read and quick to modify, but paradoxically harder to debug, because there’s no sh debugger. The TAP output doesn’t help a lot because the number used to validate an assertion lacks context.

Duplication

Because it’s written in shell, DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) is difficult to achieve. This leads to a lot of duplication between the tests, with only a few lines changed between the files. This is particularly visible on the error tests, which share an enormous amount of code and yet aren’t factorized.

TAP plan

Each time a file is modified, its TAP plan needs to be recomputed manually. I don’t think that needs further elaboration…

Performance

Performance is also one of the shortcomings. Because it’s written in shell script, it takes almost 5 minutes (with one job) to complete the suite, when it could be way less. One of the other reasons is that it contains many 1-second sleeps, which could be smaller (depending on the file system timestamp granularity) if it had better configurability.

1-second sleeps are useful to test if a time metadata has or hasn’t changed because of an operation.

Documentation

The lack of documentation, even if it isn’t really hard to connect the dots, make harder for potential contributors to understand the code.

Rewrite it in Rust

With this rewrite, we aim to solve those limitations. Other languages have been considered, namely Python and Go. However, since we had a strong preference for Rust, the test suite got oxidized!

In addition to solving the previously stated shortcomings, we want to write a Rust binary, which:

- is self-contained (embed all the tests),

- can execute the tests (with the test runner),

- can filter them according to configuration and runtime conditions,

and not in the GSoC scope but good to have:

- run tests in parallel,

- get better reports on FreeBSD’s CI infrastructure with ATF metadata support.

Test collection

The first thing we had to think on is how to collect the tests.

Since there isn’t a pytest-like package in Rust, we had to investigate

on existing approaches.

Since the result should be a binary, techniques based on cargo test were excluded.

We wanted to go first with the standard Rust #[test] attribute to collect the functions,

but the API is not public.

Cargo is the Rust package manager. This isn’t its sole task, it can also launch unit tests, which are functions annotated with the

#[test]attribute.

An experimental public implementation

is available on the Nightly channel,

but relying on Nightly for a test suite was somewhat ironic

and making harder to build the suite.

Instead, we initially implemented an approach

similar to Criterion’s one,

where a test group (criterion_group!) is declared with the test

cases.

Criterion example

use ;

criterion_group!;

criterion_main!;

Initial implementation

main.rs

chmod/mod.rs

cratepjdfs_group!;

chmod/permission.rs

pjdfs_test_case!;

...

However, as we can see, it introduced a lot of boilerplate,

so we finally decided to use the inventory

crate.

With it, we can collect the tests without having to declare

a test group or a test case.

We now just have to write the crate::test_case! macro,

which collects the test function name with

a description (which is displayed to the user),

while allowing parameterization of the test

(to require preconditions or features, iterate over file types,

specify that the test shouldn’t be run in parallel, etc.).

main.rs

tests/chmod.rs

cratetest_case!

Here, the test will not be executed in a parallel context (

serialized), require privileges (root) and will be executed over theRegular,Dir,Fifo,Block,CharandSocketfile types.

Writing tests

We now know how to collect the tests, but we still have to write them!

Again, we investigated on how to do it.

We wanted to write them like how Rust unit tests usually are.

This means using the standard assertion macros

(assert!) and unwraping Results.

Unit test example (from Rust by example)

// This is a really bad adding function, its purpose is to fail in this

// example.

This implies that the test functions will panic if something goes wrong.

Like with unit tests, which are compiled as one executable per module and

executed in parallel,

we don’t want to stop running all the tests when one fails!

This can be solved, by catching the panic

with the help of std::panic::catch_unwind.

If you want to break the test suite…

Cargo.toml

[] = 'abort'

Now that we know how to write tests, we can start, right?

Well, we can, if we don’t want isolation between tests

(and so future support for parallelization).

For example, almost all tests need to create files.

If we don’t care about isolation, we could just create them

in the current directory and call it a day.

But that wouldn’t work well in a parallel context,

therefore we need to isolate the tests’ contexts from each other.

We accomplish this by creating a temporary directory

for each test function (which the original did manually),

and by using the TestContext struct,

which wraps the methods to create files inside the said directory

and automatically clean up, among other things.

tests/truncate.rs

cratetest_case!

That would be sufficient, if we don’t consider that some tests

require functions which can affect the entire process,

like changing effective user

or switching umask.

We need to accommodate these cases if we want the runner to be able to run the tests

in parallel in the future, hence the previously mentioned serialized keyword.

It allows to annotate that a test case should be the only one running

and provide functions which should be used only in this context.

tests/chmod.rs

The function

SerializedTestContext::as_userallows to change the effective user in a controlled manner.

cratetest_case!

Thanks to the nix crate, we were able to use syscalls in Rust.

With all this and a few other methods, we rewrote the test suite

while solving the previous limitations.

What’s new?

Isolation

Now, the assertions are grouped inside a test function, which allows filtering tests with improved granularity. It also improves reporting, now that assertions are in test functions with meaningful names and descriptions.

Run example:

> pjdfstest

Which is clearer than:

> prove

Files=1, Tests=122, )

The test suite also separates tests which require privileges and skips them if the user doesn’t have the appropriated rights.

Performance

This is probably the most exciting part and Rust doesn’t disappoint on this one!

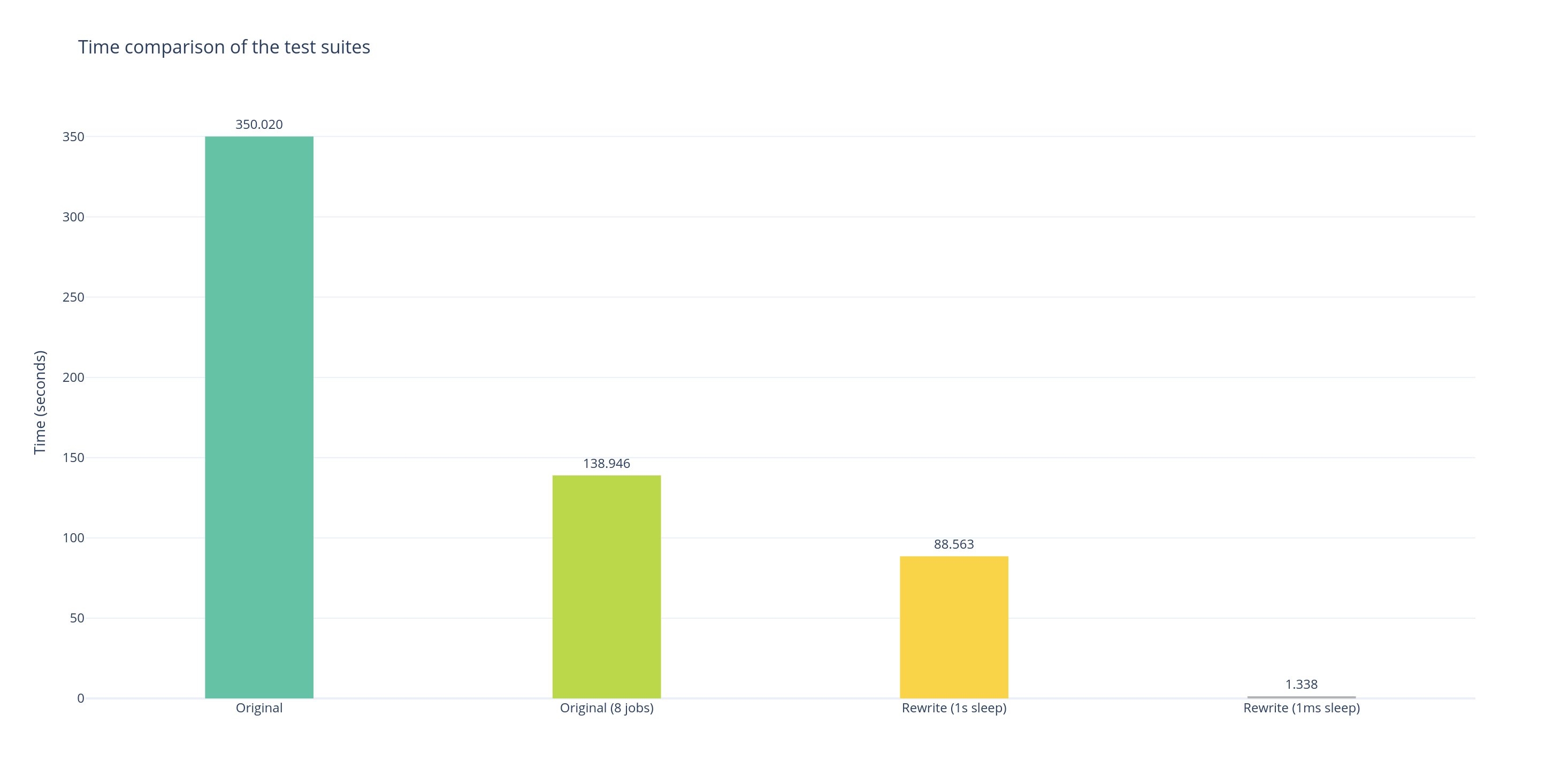

| Test suite | Time |

|---|---|

| Original | 350s |

| Original (8 jobs) | 139s |

| Rewrite (1s sleep time) | 89s |

| Rewrite (1ms sleep time) | 1s |

Tested on a FreeBSD laptop with 8 cores, on the ZFS file system. The original test suite is executed with the

proveTAP harness.

From these non-rigorous benchmarks, we can see that there is an important speed gap between the original test suite and its rewrite.

With the rewrite, the entire test suite is executed in only one second! That’s 139 times faster than the original with 8 jobs running, and 350 faster than the original with sequential tests! Even with 1-second sleeps, the rewrite is still 1.5 times faster than the original with 8 jobs running!

It’s now possible to manually specify a time for the sleeps. This greatly improves the speed, but this wasn’t the only slowness factor. As explained earlier, the old architecture in general did have a high cost. We can see this with the rewrite remaining faster even with 1-second sleep time. The rewrite doesn’t support running the tests in parallel yet, but it’s something that will definitely improve the speed with long sleep time.

Configurability

The test suite can optionally be configured with a configuration file, to specify what are the supported features or the minimum sleep time for file system to takes changes into account for example.

Configuration example

# Configuration for the pjdfstest runner

# This section allows enabling file system specific features.

# Please see the book for more details.

# A list of these features is provided when executing the runner with `-l`.

[]

# File flags can be specified for OS which supports them.

# file_flags = ["UF_IMMUTABLE"]

[]

[]

# naptime is the duration of various short sleeps. It should be greater than

# the timestamp granularity of the file system under test.

= 0.001

Debugging

Because the rewrite is in Rust, standard debuggers

(in particular rust-lldb) can be used.

It’s also easier to trace syscalls (with strace or truss),

now that a single test function can be executed.

Progress status

At the time of writing, the test suite has (almost) been completely rewritten! The original test suite had more than 7400 lines split between 225 files. This rewrite includes more than 92% of the original test suite, the exception being some granular tests. We judged that it would take too much time to rewrite all of them accurately, especially because NFSv4 ACLs are really complicated (there is no written standard to check the expected behavior, we have to rely on the implementations) and the tests are actually incomplete. Otherwise, some tests still need to be merged, as we’ve refactored the error tests, but the rewrite is already usable!

Looking forward

New functionalities can be implemented after the rewrite is done. They would improve the test suite integration along with the experience for file system developers.

ATF support

The FreeBSD’s test infrastructure is based on the Kyua test runner. It supports running framework-less and TAP test programs, but most importantly ATF -based tests. The ATF protocol greatly improve reporting for the test runner, by allowing to have test names and descriptions. It’s fairly easy to implement it for our test runner, and it would drastically improve reporting on the FreeBSD CI.

Parallelization

For now, tests are executed sequentially.

This isn’t a real problem for file systems with sub-second timestamp

granularity, but it is for the others.

We can improve the speed by implementing parallelization,

which would allow the runner to run multiple tests in parallel.

The serialized tests would need to be run separately,

but there is enough tests which don’t rely on it

to justify implementing parallelization with a noticeable speed gain.

Command-line improvements

Now that the test suite’s granularity has been improved, we can work on providing a better command-line interface, to provide filtering on file types or syscalls for example.

Appendix

Benchmark commands:

> sudo

)

)

)

)

> sudo

)

)

)

)